A geochemist who studies the workings of the deep earth and their influence on some of the world’s most explosive volcanoes has been awarded a $500,000 MacArthur Fellowship. Terry Plank, a researcher at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, joins novelist Junot Diaz, war correspondent David Finkel and filmmaker Natalia Almada in this year’s batch of MacArthur Fellows, who will receive $100,000 a year for five years, no strings attached. Maria Chudnovsky, a mathematician at Columbia’s Engineering School who studies the fundamentals of graph theory, also received a genius grant.

When not hiking up volcanoes or analyzing minerals in their ash, Plank teaches graduate students and a popular undergraduate course, Frontiers of Science. “It literally fell out of the sky,” said Plank of the prize. “I was as shocked as anybody.” She said she would continue to teach and do research, possibly “trying to do science I wouldn’t normally do” or giving some money to colleagues to pursue their creative ideas.

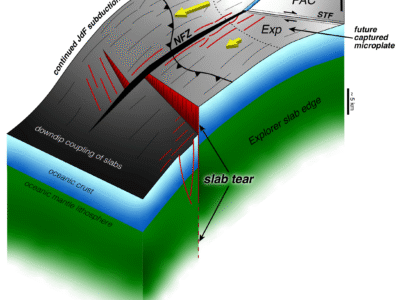

The world’s most destructive volcanoes are born where earth’s tectonic plates meet, as one plate dives beneath the other in a slow but violent recycling process called subduction. For most of her career, Plank has studied islands produced during subduction collisions: the Aleutians, off Alaska; the Marianas, off the Philippines; and the Tonga Islands, off New Zealand. In her early work, Plank discovered that long-ago ocean sediments inching down a subduction zone matched the chemical fingerprint of magma spewed millions of years later and up to hundreds of miles away by an erupting volcano. Previously, scientists thought that the subducting sediments ended up in a sort of geological trash heap along the ocean floor where the two plates meet, near deep sea trenches.

More recently, Plank has developed a chemical proxy in magmas to measure how hot the top of the subducting plate gets beneath volcanoes. Her results suggest that subducting plate tops are hundreds of degrees hotter than many geophysical models predict. In her recent area of research, Plank studies how volcanoes become explosive, fueled by water drawn down a subduction zone and superheated and pressurized. With her students and post-doctoral researchers, Plank has journeyed around the Pacific Ring of Fire to find out how much water and carbon dioxide magmas contain before they erupt, to understand why some volcanoes become more explosive than others.

Her work has helped to both identify geological hazards and uncover a missing piece of the global carbon cycle—the unaccounted-for carbon that is thought to be subducted in sediments but does not seem to appear in earth’s deep interior or emerge from volcanoes, said her colleague Peter Kelemen, a geochemist at Lamont-Doherty. “Terry has a real hard-headed desire to quantify things that people may be describing in the most qualitative ways,” he said.

At any given time, about 15 volcanoes are erupting somewhere on earth. Plank and her colleagues are currently investigating Guatemala’s Volcán Fuego, whose eruption last month forced the evacuation of 30,000 people. They are also studying one of the largest and most active volcanoes, Hawaii’s Kilauea, to see if it may have changed personalities in the past, from angry and explosive to the lava-oozing, relatively gentle giant of today. Recently, she and her colleagues collected ash and cinders from Kilauea containing crystals with tiny “inclusions” that will tell them how much water and carbon dioxide the magma held during its last apparently explosive eruption about 350 years ago. “Volcanoes cycle like this, and we’d like to know why,” she said.

The daughter of two chemists, Plank grew up in Wilmington, Del. in a house built on a schist quarry. Her father worked for the DuPont chemical company before starting his own organic chemistry lab; her mother worked at a DuPont spin-off. As a girl, Plank was fascinated by rocks and minerals. She grew up collecting them out her door and in third grade became the youngest member of the Delaware Mineralogical Society. She went to Dartmouth College, intent on becoming a geologist. She earned her PhD. at Lamont-Doherty and continued her teaching and research at the University of Kansas and Boston University, before returning to Lamont in 2008. In 1998, she won two awards for early career achievement: the Geological Society of America’s Donath Medal and the European Association of Geochemistry’s Houtermans Medal.

Plank is the second Lamont scientist to win the MacArthur award; seismologist Paul Richards, an expert in detecting nuclear blasts who later published pioneering research on earth’s core was one of the initial recipients. Lamont-Doherty is a member of Columbia University’s Earth Institute. Other Earth Institute recipients in the past have been demographer Joel Cohen, who studies global population growth; ecologist Ruth DeFries, who studies human transformation of earth’s surface; and agronomist Pedro Sanchez, whose work on soils has helped boost agricultural yields in many developing countries.