By Julian Spergel

The Rosetta team has been in Antarctica for a week now and we’re almost done with unpacking and testing all of our equipment. Our first survey flight of the season is scheduled for the end of the week.

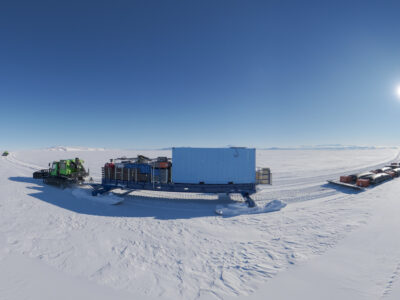

The first few days of our time in Antarctica was spent on safety training and ‘waiting on the weather’. Each step of our set-up process, which includes receiving cargo, installing electricity in our tent, unpacking our boxes, and building disassembled instruments, needs to wait for safe weather conditions, which in Antarctica is by no means guaranteed. Our workstation is a yellow Jamesway tent on the airfield named Williams Field. It is about a 30 minute drive from McMurdo Station, on a nearby section of the Ross Ice Shelf.

Even though our tent is within a short drive of McMurdo Station (a small town with most of the safety and logistical equipment on the entire continent), we still need to prepare ourselves for sudden, extreme weather. Every time we leave the relative safety of McMurdo, we carry our Extreme Cold Weather equipment and our tent has emergency food and sleeping equipment.

Driving onto the ice shelf is a surreal experience: the landscape is a nearly featureless white, flat expanse, with only tiny buildings and the black, slug-like shapes of lounging seals to break up the uniform whiteness. When there are low-lying clouds, the ice and the sky seem to meld into a single white area.

After two days of unpacking, our little tent is becoming very cozy. We have a line of tables for our computers and printer, a coffee machine and two gas heaters, a number of powerful external hard drive units called a Field Data Management System. Our scientific instruments are coming together, as well. To keep both ourselves and our electronics warm, we keep two heat-stoves running all the time. In preparation for our flights, we’ve split into two shifts, one in the day and one at night. Myself and six other people spent last weekend transitioning our daily schedules to sleeping during the day and being awake to work over the night. Due to the polar latitude, the sun never goes down, so the two shifts experience nearly identical levels of light. Yet my sense of time is very confused and I often forget what day of the week I am currently in.

Before we start recording and processing data from our first survey flights, we need to rebuild the instruments that were deconstructed for shipping, and calibrate them to make sure the data recorded is accurate. With round-the-clock activity, we have set up everything in only a few days. One of the needed activities was hanging the gravimeter onto a freely-suspended gimbal with bungee cords so that it is stabilized against the movement of the plane. Many of the components of our sensors are very delicate, but a large number of the external components are larger, easily adjusted, and could be found in a hardware store. Unlike other fields of science, polar fieldwork operates best when adjustments can be made while wearing heavy gloves.

Additional set up involves installing “base stations” to record a background level of magnetics and GPS information. A five-minute walk across the ice from our tent, we have erected two yellow tripods and partially buried a small box of sensors. The instruments are powered by a small solar panel that we set up nearby. Each tripod needed to be secured against wind by tying the legs to bamboo poles we buried in the snow as an anchor. The snow on the ice shelf is incredibly dry and compact, so digging into it feels like digging through Styrofoam. Filling in the holes with snow, stamping on it, and waiting only a few minutes allows the snow to harden to a strength similar to concrete.

Our first test flight is scheduled for the end of the week. We will fly one of our survey lines and make sure that the instruments’ readings are accurate so that on future flights we will know that the instruments are working properly. In addition we will be ensuring that each of the instruments functions by checking sections of the data after every flight. My assigned role once flights are running regularly is to analyze the ice-penetrating radar during the night shift.

For more information about Rosetta-Ice, check out our website and the archive of this blog. Have questions about Rosetta-Ice or about living and working in Antarctica? Feel free to email your question to juliansantarctica@gmail.com, and I will try to answer it in the next blog entry!

Julian Spergel is a graduate student at the Department of Earth and Environmental Science at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and will be blogging from Antarctica. He works with Professor Jonathan Kingslake on analyzing spatial and temporal trends of supraglacial lakes on the Antarctic Ice Sheet using satellite imagery.