Despite its tropical climate and floodplain location, Bangladesh—one of the world’s most densely populated nations—seasonally does not have enough freshwater, especially in coastal areas. Shallow groundwater is often saline, a problem that may be exacerbated by rising sea levels. Rainfall is highly seasonal and stored rainwater often runs out by the end of the dry season. And contamination by naturally occurring arsenic deposits and other pollutants farther inland further depletes supplies of potable water, which can run desperately short during annual dry seasons. According to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, 41 percent of Bangladeshis do not have consistent access to safe water.

Hoping to ease the crisis, researchers from Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, which is part of the Columbia Climate School, led an exploration for new freshwater sources along the Pusur River in the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta. They recently published their results in the journal Nature Communications.

The results, which indicate vast freshwater reservoirs beneath coastal Bangladesh, could help millions of people who lack access to potable water. It is also a demonstration of a new technique for sensing water sequestered deep underground, raising the possibility that hidden reserves could be available in other water-starved regions with similar geological histories.

While some experts knew about these reservoirs, hundreds of meters belowground, their location and extent had not been previously established. Finding freshwater deep underground was thought to be hit or miss.

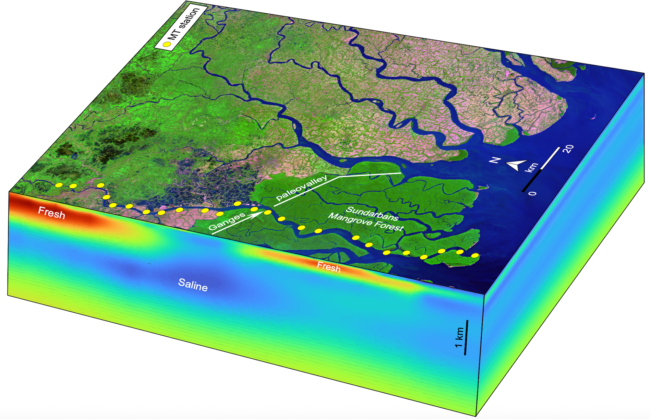

The researchers used a technique called deep-sensing magnetotelluric soundings to measure faint electrical currents in sediments up to a few kilometers beneath the delta. Because freshwater is less electrically conductive than saltwater, the researchers were able to map the distribution of freshwater. They identified two reservoirs: one that extends 800 meters deep and stretches about 40 kilometers along the northern part of the surveyed area, and another to the south that reaches a depth of 250 meters and stretches 40 kilometers. The northern reservoir likely extends tens of kilometers beyond the survey area.

The reservoirs appear to have been formed by geological processes during the last 20,000 years, as falling sea levels first exposed once-submerged land to fresh water before inundation by rising sea level sealed it off. The saline water separating the two reservoirs correspond to the location of the ancient Ganges River. The valley it formed when sea level was low was flooded with salt water when sea level rose. Thus, the saltwater separating the two fresh reservoirs correspond to the location of the ancient Ganges River.

“During the last ice age, sea level was 400 feet lower and the shoreline was 80 to100 miles farther seaward,” explains study co-author Michael Steckler, a geophysicist at Lamont. Rainfall and floods filled aquifers with freshwater; meanwhile the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers delivered sediments eroded from the Himalayas, with the finest spread across the delta’s lower reaches. When sea levels rose again and flooded the land, says Steckler, “muddy sediments trapped and preserved the freshwater below.” The buried positions of the rivers 20,000 years ago can be used to identify where the deep groundwater is fresh or saline.

According to Steckler, it’s not uncommon in Bangladesh for deep wells to be dug without knowing how much water is present and how much can be extracted. This study provides a framework for mapping where the fresh water can and cannot be found.

The full-size dimensions of the reservoirs and how much water they contain has yet to be determined, but it could be on the order of 10 billion cubic meters, or about 4 million Olympic-sized swimming pools. Other open questions include the rate at which water can be safely extracted. If too much is removed too quickly, it could pull saltwater deposits overlaying the reservoirs down into the freshwater, rendering it saline.

“To use these kinds of groundwater, people need to carefully plan the water management ahead of time,” says Huy Le, a geophysicist at Lamont and the study’s lead author. Sustainable management is essential—but Le also notes that with time, perhaps a few thousand years, natural salinization processes will eventually turn the reservoirs salty. “It will disappear if we don’t use it,” he says.

Although the study focused on Bangladesh, the researchers say it has implications elsewhere: Similar reservoirs may be found in other coastal deltas and continental margins with similar geological histories to Bangladesh. “Sea levels fluctuated everywhere. It’s a global phenomenon,” says Le.

The study was coauthored by Kerry Key, formerly of Lamont and now at Deep Blue Geophysics; Nafis Sazeed, New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology; Mark Person, New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology; Anwar Bhuiya, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh; Mahfuzur R. Khan, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh; and Kazi M. Ahmed, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh.