By Julian Spergel

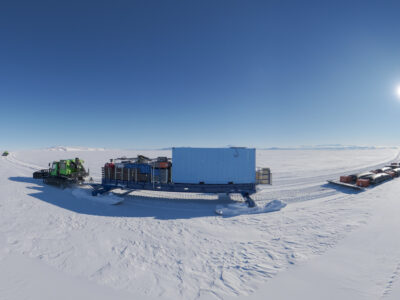

After what seemed a multitude of small setbacks due to weather and plane repairs, Rosetta’s third season came to an end amid a flurry of last minute flights, packing, and saying goodbye to our new friends. The last few days flew by as we cleared out our tent on Williams Field, disassembling our equipment, and returning borrowed equipment to the proper departments.

Packing down here is done carefully. Everything we had brought down to the tent had to be checked off a list, packed in its proper container, labelled for shipping, placed on a metal pallet, weighed and labelled by weight for packing, put back on a metal pallet, and finally sent off for shipping. I’m glad my own things did not need to go through such a rigorous process, though I bet I would lose fewer possessions if I was this meticulous! Among the 14 of us, the whole process went by quickly, and the tent that we had considered our little corner of Antarctica emptied in just two days.

But enough is never enough when you have traveled so far for data. Almost out of nowhere we were given a surprise opportunity to fly one of our survey lines on the second-to-last day of our Antarctic season and we jumped at it! While it wasn’t possible to unpack all of our instruments, the careful packing and labeling of the pallets allowed us to readily locate what we needed. In a final burst of unpacking we had our gravimeters together and were ready to go. There is always time for more data.

For the return trip I was tasked with carrying one of two copies of our scientific data (there is always redundancy in data this hard to collect). I carried a hard plastic suitcase filled with a dozen thumbdrives and more than 70 hard drives, equaling 70 pounds of memory, from McMurdo Station, Antarctica to New York City. Some readers may be wondering why we used such a physically demanding method of sending data home. Even in 2017, there is no means of transferring data as safely and as quickly as a graduate student carrying a bag of hard drives! After some huffing and puffing, and some odd looks from security personnel, I delivered the data to Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory outside NYC for our archivists to put onto the server.

What have we accomplished this third field season? Ultimately, after flight cancellations due to more than a week of harsh weather and airplane technical issues, we were able to complete fourteen of the eighteen flights we planned for this Antarctic season. In total, we had roughly 260 hours of flying over an area the size of Texas.

The goal of the Rosetta-Ice project was to use airplane-mounted sensors to create a 10-km resolution grid of geophysical measurements of the Ross Ice Shelf’s glaciology and geology. After three Antarctic field seasons, our mapping is finished. In the northern (bottom) two-thirds of our survey grid we have created a 10-km resolution map, and in the remaining third of the surveyed area we have a 20 km-resolution map. The data collection phase of our project is over, but the analysis of the data is ongoing.

With the new, higher resolution map of the Ross Ice Shelf and the underlying seafloor, previously unseen small-scale features can be identified and studied. Research assistant Isabel Cordero has been working on ‘picking’ the ice layers of the radar echograms, identifying the layers of accumulated ice from the various glacial sources, for the past year. I’m looking forward to the day when, in a few months time, we print out all the radar echograms that we collected, with the ice layers and interesting points labelled for everyone to peruse.

In the coming months, we will be presenting our initial findings. But for several years we will continue to dig in to the data, as we seek to answer the research questions that led our project in the beginning. The goals for Rosetta-Ice were to answer questions about the conditions on top of and inside the Ross Ice Shelf’s ice, as well as the conditions in the ocean water circulation and rocky bed beneath the ice, and look at linkages. The most exciting aspect of finishing a scientific project is not just what questions can be answered, but what new questions will develop as we learn more about the Ross Ice Shelf and Antarctica as a whole.

For further updates about our project keep checking back to our project site.

This will be my final blog entry, and I would like to finish on a personal anecdote. At the beginning of my time on this blog, I wrote about how coming to Antarctica was a personal goal of mine. On my last hike in Antarctica, a five-hour trek to a large rock crag called “Castle Rock,” I had a moment where, as I looked out over the landscape, I felt a sense of completion. Standing in the middle of a flat, windswept field of snow and ice and watching the snow-covered volcano Mt. Erebus smoke white steam into the sunny blue sky, I thought: “This is Antarctica. All my life, I have imagined what it would be like to be here, and here I am, and it is even more majestic than I thought.” I did my best to memorize every detail of the scene: the cold, the silence, the vividness of the colors. There was so much of Antarctica that I would never be able to see, and the freshness of my memories of being here would soon fade, but if I could just remember this moment, it would be enough.

I was so lucky to be able to visit this remote corner of our planet. I only wanted to return again soon, to see and learn more. Before I knew it, I was stepping out of the plane in Christchurch, inhaling my first scents of plant life in over a month.

Julian Spergel is a graduate student at the Department of Earth and Environmental Science at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. He works with Professor Jonathan Kingslake on analyzing spatial and temporal trends of supraglacial lakes on the Antarctic Ice Sheet using satellite imagery. He graduated with a B.S. in Geophysical Sciences from the University of Chicago in 2016. He has been involved with a number of diverse projects and has been interested in polar studies since early in his career. His fieldwork has brought him north to the Svalbard Archipelago and south to McMurdo Station, Antarctica.

Learn more about previous years’ research, here.

For more on this project, please visit the project website.