By Jen Lamp

This blog post was originally drafted on December 5, but couldn’t be posted until now because the Antarctic fieldwork site lacked an internet connection. Read more about the project here.

The weather held out for us, and we made it to our Beacon Valley campsite on Dec. 1 as planned. Our camp put-in ended up requiring four helicopter trips: two for slings, one to carry us and cargo, and a fourth for extra cargo that couldn’t fit on the other helicopters. The fourth helicopter also brought us two pizzas from McMurdo that we promptly demolished.

The most common questions I’m asked after a field season are about life at camp. There are camps in the McMurdo Dry Valleys with permanent and heated structures, internet, and relatively reliable power, but we do not have those amenities in Beacon Valley. What we do have are:

- A communal endurance dome tent with a propane camp stove for cooking, eating, and socializing (and also where I sleep)

- A Scott tent with a white gas stove where Missy and Kate sleep

- A Scott lab tent for doing work that can’t be done out in the cold/wind

- Two 1kW Honda generators that we run intermittently to charge computers, radios, camera batteries, etc.

You will notice that the above list does not contain a sink, shower, or bathroom. All the waste we generate at camp has to be collected and sent back to McMurdo for processing. From there, it is then packed and shipped back to the U.S. per the Antarctic Treaty. We pee in 1-liter Nalgene bottles, then pour it into larger 5-gallon containers that are sent back by helicopter to McMurdo when full. Solid waste is collected in the “Johnson Box”: a wooden box with a foam seat placed over a 5-gallon bucket, that is set outside behind a large boulder (i.e., a wind break). It may sound miserable, but it has one of the best views from a “toilet” anywhere in the world.

Because we have to collect all liquids, we run a zero-greywater camp, meaning that we do not produce excess dirty water. Otherwise, after a few weeks all that water would add up to a lot of extra weight to fly back to McMurdo, which equals extra helicopter trips. This means we do not wash our hands, dishes, or anything else, and all cooking has to be done in a way as to not produce left-over fluid. The one Antarctic-specific talent I’ll boast about is that I’m awesome at cooking pasta with no excess water—it’s super starchy, but usually tastes good enough when you’re cold and exhausted.

My daily routine consists of waking up around 06:30 in the endurance tent, starting the propane stove to heat up water (sourced from a nearby snowbank), and making our daily check-in call to McMurdo over the satellite phone. These check-in calls are really important: if we’re even a minute late, MacOps—the communications lifeline of McMurdo—alerts members of the Emergency Operations Center. I sleep with a small bag containing items that I need to keep warm for the morning: batteries for my camera and the Iridium phone, sunscreen, my iPod, etc. Kate and Missy get to the tent around 07:15. We eat breakfast and drink coffee, then get ready to work.

Meals are fairly simple: breakfast is normally oatmeal with some muesli and dried fruit. Lunch varies depending on whether we’re working at camp or hiking, and for dinner we rotate between about 7 or 8 pre-planned meals. The overall favorite so far is “stroganoff” made with egg noodles, canned mushrooms, dehydrated tomatoes, and powdered sour cream. Because we’re so isolated and are around each other 24/7, a major factor in having a productive field season is the social dynamics at camp. We’re lucky in that we all get along and work together well; when we do need some quiet time alone, we usually read or take short walks around camp.

On the science side, things have been going great for us. We spent the day after arriving at camp trying (and ultimately failing, sadly) to reach McMurdo using our HF radio, setting up our UNAVCO GPS base station, and walking around camp in search of the four boulders we want to instrument with the AE sensors. We’ve decided to choose four dolerite boulders, all with slightly different crystal sizes and erosional patterns, in hopes that we can compare how each affects the frequency of microcracking. Once we settled on the best candidate boulders, Missy decided that instead of calling them Rock 1, 2, 3, and 4, we should name them after our mothers. So, we have:

- Pambi: a rounded, coarse-grained dolerite boulder undergoing granular disintegration

- Frankie: a rounded, medium-grained dolerite boulder

- Theresa (hi mom!): a tabular, medium-grained dolerite with a large flaking weathering rind

With only three mothers for our three-person team, we needed one more name for the last boulder. We quickly settled on Ruth Bader Ginsburg (Ruth Boulder Ginsburg?). RBG is a tabular, fine-grained dolerite boulder with a well-formed, smooth weathering rind. We decided to set the boulders and equipment out on a flat area around 50 to100 ft from camp. We set up our yellow Scott lab tent, and carefully moved the four boulders inside.

And then, on Dec. 5, our epoxy arrived. We’ve had quite the epoxy saga this week, which requires a bit of background to fully understand.

In order to attach the acoustic emission sensors, thermocouples, and surface moisture sensors to our boulders, we need an adhesive that we know (a) will dry/cure and survive in the cold, and (b) has properties that allow the sensors to do their jobs. For the AE sensors this means being able to transmit elastic waves effectively between the rock and sensor, and for thermocouples, having a high thermal conductivity to transfer heat between the rock and thermocouple. Being the ever-paranoid researcher that I am, I tested a few types of epoxy/cement in a freezer back at LDEO, and sent down multiple types and tubes of epoxy and adhesive cement. However, as I later discovered, hazardous cargo that is shipped to Antarctica is combined into larger containers to save money. In theory this is fine, except that when one person/group doesn’t properly label their hazardous material, or tries to send too much of something with a weight or volume limit, the entire container gets held up.

Unfortunately, our epoxy (and some extra batteries) landed in one such troubled container, and when we arrived at McMurdo, we were told some of our cargo was still stuck in Port Hueneme, CA, and some of it was in an unknown location, transiting between CA and Christchurch, NZ. Once we realized the epoxy wouldn’t reach us before heading to the field site, multiple people at McMurdo tried to find us something suitable on station but unfortunately, they didn’t have what we needed. It was nerve wracking being at the site without knowing when or if we’d be able to actually attach any of the equipment to the boulders, but thankfully our Dec. 5 helicopter delivered a beautiful box covered in hazardous warning stickers that contained two of the four types of epoxy I’d mailed – and luckily exactly the two types that we were hoping to use!

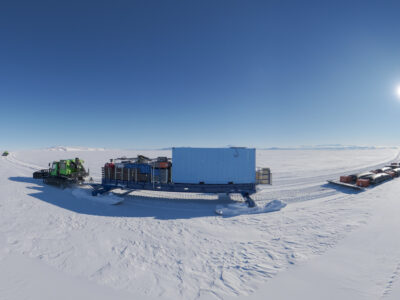

After the arrival of the epoxy, Kate and I spent the afternoon setting out three of the four 140W solar panels that will charge the batteries for the acoustic emissions monitoring system. We piled the mounting brackets with rocks, and will eventually attach staked guy wire lines to keep the large panels from sailing away during Beacon Valley’s frequent wind storms. While Kate and I were fighting with some unfortunately placed bolt holes, Missy spent the afternoon in the lab tent making a detailed catalogue of the surface features of each boulder, including the locations of any existing cracks and salt encrustations. The next step is to start attaching all of the sensors!