Glaciers in one part of West Antarctica are melting at triple the rate of a decade ago and have become the most significant contributor to sea level rise in that region, a new study says.

The study found that the glaciers in the Amundsen Sea Embayment of West Antarctica have shrunk by an average of 83 gigatons a year for two decades—the equivalent of the weight of Mount Everest every two years. And the loss rate is accelerating: The scientists estimate ice loss at 102 gigatons per year for 2003-2011.

The paper reinforces two studies from last spring that suggested that the West Antarctic Ice Sheet that feeds the glaciers has become increasingly unstable and may be on an inevitable path to disintegration. That process could take a few hundred years; but the West Antarctic Ice sheet, just one portion of the massive slab of ice covering the continent, holds enough water to raise sea levels globally by 16 feet. Though not imminent, that would have devastating effects on coastal communities where hundreds of millions of people live, along with the natural ecosystems in those regions.

The most recent findings look back at measurements taken from 1992-2013, including work done by scientists from the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and other institutions as part of NASA’s IceBridge project. The study, by scientists at the University of California, Irvine, and NASA, reconciled data from four different measurement techniques and used it to estimate ice loss over the past two decades.

“The mass loss of these glaciers is increasing at an amazing rate,” said scientist Isabella Velicogna, jointly of UC-Irvine and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. Velicogna is a coauthor of the paper, which has been accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

“It’s really important to be able to compare results from different methods and encouraging to see this level of agreement in the numbers,” said Kirsty Tinto, a researcher at Lamont with a decade of experience in the Antarctic, who was not involved in the paper. “It’s very clear that the Amundsen Sea Embayment is losing mass, and the numbers on that are becoming increasingly well constrained.”

Tinto and Lamont colleague Jim Cochran returned recently from the latest round of Operation IceBridge surveys, flying out of Chile and over the Amundsen Embayment. IceBridge has been flying missions since 2009 to cover a gap in satellite coverage, using various instruments to collect data on what’s happening on and under the ice while NASA prepares to launch a new satellite.

“The study noted that most of the change was attributed to changes in the glacier dynamics—meaning the way that glaciers move the ice out to sea—while the large variations in surface mass balance averaged out over a couple of decades,” Tinto said. “So it’s important for prediction that we understand how those dynamics work. That’s something that the airborne campaigns are particularly good for, because they measure a lot of things at once—from the surface down to the bed of the glaciers.”

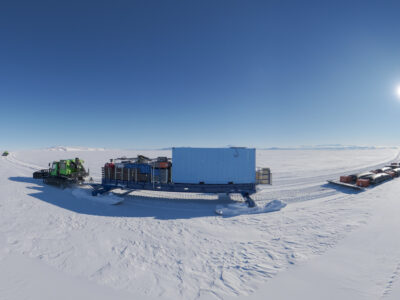

Another group of Lamont scientists, are currently operating out of McMurdo Station in Antarctica with the IcePod project. IcePod uses a Lamont-designed, integrated set of airborne instruments that can measure in detail both the ice surface and the ice bed. Lamont’s Margie Turrin is blogging about the work here. For an overview of who from Lamont is doing what in Antarctica,read this blog post from Lamont’s Rebecca Fowler.

Further reading:

Read a news release from the American Geophysical Union, which publishes Geophysical Research Letters.

NASA has a webpage on ice loss in Antarctica.

You can follow the research on NASA’s Twitter account, NASA ICE.

For more on IceBridge, check out NASA’s IceBridge blog, and the Lamont IceBridge page.

What’s eating away at the ice shelves? A fresh news story at Science online looks at new research pointing to warming ocean water as a possible culprit.