By Caitlin Boas

Last fall marked the five-year anniversary of Hurricane Sandy. When Sandy hit, I was living in Crown Heights, a neighborhood which, as its name might suggest, sits at relatively high elevation compared to the rest of Brooklyn. Like most people who rely on a bike for their main source of transportation, I’d assigned a portion of my brain to recognizing and storing topographic variation along my routes. From school to home: uphill. From home to school: downhill. From school to the beach: flat. From the beach to many of my friends’ neighborhoods: very, very, very flat.

Apart from strategizing low grade bike routes, this generalized knowledge of New York City’s elevation profile distilled in me both cautious relief and an unsettling dread as Hurricane Sandy began to unfold. Relief because although my apartment was below street level, it was both inland and uphill. And dread because my friends’ neighborhoods across the city were barely above sea-level and significantly closer to the shore. Authorities warned that, in addition to high rainfall and severe winds, low-lying areas near the coasts should brace for an 11-foot surge of seawater on top of an already high-tide. I realized much of the city would become fully inundated.

New York City as a whole isn’t particularly complex in its topography. Elevation maps highlight the high proportion of low-lying land distributed across the boroughs, especially in lower Manhattan and the Atlantic-facing regions of Brooklyn and Queens. Morningside Heights, my current neighborhood and the home of Columbia University’s main campus, make it easy to forget that New York City is made up of a number coastal islands, which are sidled up directly on the Hudson River and the Atlantic Ocean. This coastal positioning, coupled with a somewhat muted elevation profile, were key factors that established New York City as a major port, and later fostered its rapid growth and development into the metropolitan hub that it is today.

The geographic features that once defined this city now pose significant threats against it. It is projected that my generation will witness sea levels rise by three feet in New York, and we’ll experience more frequent and more severe coastal floods. Last year’s hurricane season, despite sparing the greater New York City area, was particularly devastating—and climate models predict that these events will only get worse in the decades to come. Aggressive and short-sighted urbanization, especially when paired with the effects of climate-change, leaves our city vulnerable.

The consequences of an ill-prepared city manifested in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. The storm surge exceeded expectations, amplified by the consequences of intense urbanization, which has paved over our shorelines with concrete and other impermeable construction materials. This has hardened most of New York’s naturally protective barrier islands, bays, and inlets—environments that absorb the brunt of extreme storm events. The communities that had developed on these natural protective barriers experienced the most severe consequences of the storm. Flooding in coastal neighborhoods across Queens, Brooklyn, and Staten Island left more than 40,000 New Yorkers homeless. Due to the heavy winds, curtains of fire blazed through the Rockaways, completely leveling the seaside community of Breezy Point. I could smell the smoke from my apartment, some 12 miles away.

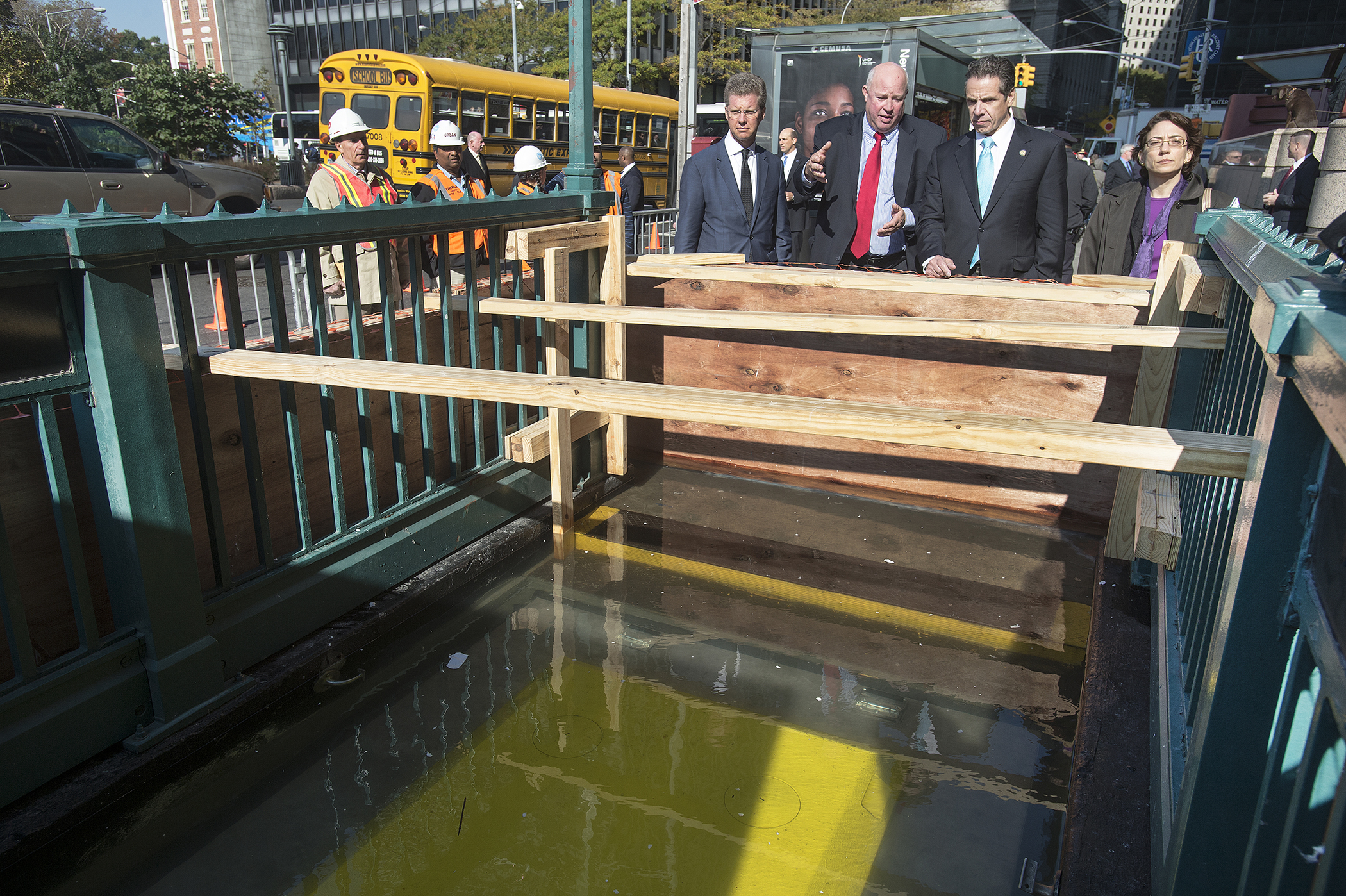

The amplified storm surge caused further destruction to the city’s infrastructure. Precautions taken to protect the Con Edison power plant on the edge of Manhattan’s east side were inadequate. The station flooded, causing extensive system failure throughout the metropolitan grid. This triggered a prolonged blackout across the city, and required the evacuation of hospitals which no longer could provide power or clean drinking water. The flooding spilled into the underlying Canarsie Tunnel which carries the L subway line under the East River, rushing seven million gallons of seawater through a key section of the subway’s infrastructure. Walking across the bridges, the only infrastructure left to navigate across the East River, became the standard mode of transportation between Brooklyn and Manhattan. Response to these damages cost the Metropolitan Transit Authority billions of dollars and is still underway: an 18-month suspension of service to the L line commences in 2019 while repairs continue. In the wake of Sandy, MTA spokesperson Adam Lisberg cautioned, “We’ve suffered extensive damage. You can ride your train to work every day, and you think it’s fine, but it’s not.”

In many respects, New York City has responded by building back better than before, with plans that encourage resilient development strategies. Con Edison has taken further precautions by raising its power plant’s electrical equipment to heights of 20 feet or more. The MTA implemented a $7.6 billion program to install flood protection barriers. City planners continue to consider building berms around lower Manhattan to keep the water from rushing into the streets and basements of its buildings. Yet the city continues to help New Yorkers rebuild in our most vulnerable coastal neighborhoods—an approach that is short-sighted at best. In this regard, our city’s resiliency strategy feels more stubborn than informed.

With 520 miles of coastline, New York is the epitome of a coastal city. Although spared from 2017’s devastating hurricane season, many climate scientists agree that future years may not be as forgiving. While building for a more resilient future may lessen the impact of rising sea levels and severe storms, this strategy alone isn’t enough in the face of climate change. Independent of threats from worsened storms, our most low-lying neighborhoods now experience tidal flooding regularly, isolating communities and completely disrupting a normal way of life multiple times a month. Subsidizing reconstruction in these high-risk coastal zones is nothing short of irresponsible—billions of tax dollars aside, it’s placing people right back in harm’s way.

Caitlin Boas is a student at Columbia University, graduating with a Masters of Public Administration in Environmental Science and Policy this May. A long time New Yorker, she holds a degree in Earth and Environmental Sciences from CUNY Brooklyn College and previously worked as a paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural History. Caitlin believes that city landscapes and communities must proactively adapt to our changing planet, and looks forward to promoting sustainable-minded initiatives across the urban landscape. Although no longer in an official capacity, she can still be found hunting for fossils and sharing her love for all things science across New York City.